Brief History of Ikebana

Ikebana is the ancient Japanese art of arranging flowers, documented as far back as 1486. The art, and the companion discipline of kado, or the way of flowers evolved from the ritual of randomly thrown floral offerings to the spirits of the dead in the birthplace of Buddhism – India. When Buddhism came to Japan during the 6th century via China, the flower practice came along with it. By the 10th century, temple priests, who were primarily responsible for floral offerings started the use of containers. Later with a more relaxed attitude towards Western culture in Japan, the world started to witness the practice of ikebana occuring not only in Japanese homes but also around the world.

Origins of Banmi Shofu Ryu

Banmi Shofu Ryu originated from Shofu Ryu, which, like all other Ikebana schools had roots from the first school of Ikebana – Ikenobo. Shofu Ryu, the parent school of Banmi Shofu Ryu was one of many “modern” Ikebana schools that emerged during the 15th century, straying from the stricter rules of ikenobo. It appealed to the European taste because of its clever adaptation of traditional kado principles to new (sic) Western conditions. Its name translates to pine or living breeze, and Shofu creations express a spirit of naturalness, as effortless as the wind on the pines during a hot summer day. True to its heritage, Banmi Shofu designs show both fluidity of line and fidelity to the way plants grow in nature – quite contrary to what images might come to mind when one considers that the founder of Shofu Ryu was a true, practicing samurai, (Oshikawa, 1939). Its rules of ikebana engagement originated from published and translated written and oral traditions handed down by Josui Oshikawa, Bansui Ohta, and Bessie Banmi Fooks. To this day Banmi Shofu traces its origin to Shofu Ryu and sees itself as its contemporary expression with a consistent characteristic use of driftwood in its designs.

Complex Moribana by Bessie Banmi-sensei

Hallmark Banmi Shofu multiple moribana design by Bessie Banmi Fooks, using heirloom driftwood from Waialua, HI and the Philippines.

Floral and line materials include heliconias, three varieties of torch gingers, and fennel. Containers include three small and one large ceramic moribana suiban. Table surface is covered with blue furoshiki. and dried seaweed.

Designs, Hanko, Connecting with the Founding Samurai

Double Hashibana Uate

Double Hashibana Uate

Double Hashibana Uate

A new iemoto has the responsibility of introducing something new shortly after installation; Ric Bansho introduced a new style, hashibana - which literally translates into flower bridge - symbolic of the connection between 5th century traditions and contemporary designs. Hashibana is expressed in three designs: Hashibana Maru (globular); Uate (tall, narrow & wide); and Saba (short, narrow, and wide) all coming with very specific container requirements.

Style: Hashibana Uate, an Emerging Banmi Shofu design but Steeped in 6th Century kaden

Container: Z-Gallery Uate sitting on vintage Japanese golden brocade Black, Orange & White Football Chrysanthemums, Long Needled Pine, & Waialua Driftwood

Samurai Spirit

Double Hashibana Uate

Double Hashibana Uate

Conforming with Tradition,

Flowing into Now

Through flowers, I am one with nthe founding Samurai. He was rough & aggressive, yet tender & delicate with his kado. Like it or not, legacy evolves.

Free -form prose as in the featured example provides a means of expression for the Banmi Shofu practitioner with an alternative to haiku or story around the created flower design. In this case, it is Ric Bansho‘s ode to the founding samurai, describing how he channels the samurai‘s Zen posture while balancing gentleness and strength used in battle.

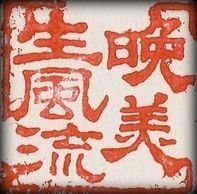

Hanko

Double Hashibana Uate

Viewing Banmi Shofu Flower Designs

Banmi Shofu Ryu hanko evokes the spirit of its flower designs. In evolving Shofu tradition into Banmi Shofu, Iemoto Bessie Banmi Fooks (1996) stated: "I used natural materials in simple lines provoking movement and symbols that in turn achieved serenity and tranquility.

All Banmi Shofu Ryu official documents and certificates of competence and artistry come with this honorable stamp of iemoto approval as well as the iemoto’s hanko.

More information about Banmi Shofu Ryu flower designs are available in https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Banmi_Sh%C5%8Df%C5%AB-ry%C5%AB

Viewing Banmi Shofu Flower Designs

Viewing Banmi Shofu Flower Designs

Viewing Banmi Shofu Flower Designs

Banmi-sensei said, "I could view the designs from any angle. They were simply the end product of a process that connected me spiritually with plant and driftwood materials. This has been my experience that began in Japan years ago. I continued to learn from Bansui Ohta sensei, and transplanted what I absorbed in Japan to Hawaii, and to the many places in the world where I traveled and connected with friends who love flowers. (Moribana Kansuike design by Ric Bansho-sensei created during a live demonstration in Tokyo's Art Laksy Gallery, 2014)

Perspective

Viewing Banmi Shofu Flower Designs

Driftwood Is Container Sometimes

When creating flower designs, looking at flowers in their natural habitat allows a viewer to experience different perspectives of the same floral or line (stem, leaf or branch) material. Sometimes the back is as poetic, if not more than the front, as shown in this pristine white Phalaenopsis against the teal tint of the pool water.

Driftwood Is Container Sometimes

Viewing Banmi Shofu Flower Designs

Driftwood Is Container Sometimes

Possibilities are limitless in Banmi Shofu ikebana - for example this Gendaika (freestyle) design by Dolly Tu-sensei from Taipei, the Republic of China features a large driftwood forming the base and container for two large Proteas, with smaller driftwood pieces intentionally placed to cradle cascading China Berry fruits - telling a story of contrast, comfort and beauty.

Copyright © 2019 Banmi Shofu Ryu of Ikebana - All Rights Reserved.

Powered by GoDaddy Website Builder